Copyright Tony Whitehead.

Visit his pay-per-view website of parish register entries and census returns for the entire county at www.durhamrecordsonline.com Your ancestors may well be there.

Christ Church, New Seaham

In September 1828, the town and port of Seaham Harbour were founded. As this was part of the parish of Dalton-le-Dale most of the baptisms, marriages and burials from the new community were recorded at St. Andrew’s in Dalton village. St. Mary the Virgin continued to serve only [Old] Seaham village, Seaton-with-Slingley and outlying farms. In 1845 St. John’s at Seaham Harbour opened its doors after a new parish was created and detached from St. Andrew’s. Henceforth most of the events of Seaham Harbour were recorded at St. John’s. 1838 – Sinking of Murton Colliery began. Events from this new community were recorded at St. Andrew’s. 1844 – Sinking of Seaton Colliery commenced. Events from this new community were recorded at St. Mary’s. 1849 – Sinking of Seaham Colliery began. Events from this new community were recorded at St. Mary’s. New Seaham colliery village was constructed from 1844 onwards. The new community was within the parish of St. Mary the Virgin at (Old) Seaham until the building of New Seaham Christ Church in 1857 and the creation of a new parish in 1864. It was lumped with Old Seaham for census purposes until relatively recently.

Available Parish Registers at Durham Record Office

St. Mary the Virgin, (Old) Seaham, Baptisms 1646-1861

St. Mary the Virgin, (Old) Seaham, Marriages 1652-1967

St. Mary the Virgin, (Old) Seaham, Burials 1653-1966

Christ Church, New Seaham, Baptisms 1857-1967

Christ Church, New Seaham, Marriages 1861-1970

Christ Church, New Seaham, Burials 1860-1954

Wesleyan Methodist, New Seaham Cornish St., Baptisms 1870-194

Also incorporated this site (www.durhamrecordsonline.com )are the following records which are not currently available at Durham Record Office.

St. Cuthbert RC, New Seaham, Baptisms 1934-1999

St. Cuthbert RC, New Seaham, Marriages 1934-1999

St. Cuthbert RC, New Seaham, Burials 1934-1999

HTML clipboard

| 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | |

| Seaham (Old & New) | 115 | 121 | 103 | 130 | 153 | 729 | 2591 | 2802 | 2989 | 4798 | 5285 |

All census returns 1841-91 inclusive for the village have been transcribed and incorporated at www.durhamrecordsonline.com

Growth of the Village of New Seaham 1861-91

History of Seaham Colliery

HTML clipboard

| 1861 Census | 1871 Census | 1881 Census | 1891 Census |

| West Row (23) | School Row/Vane Terrace (25) | Vane Terrace (23) | Vane Terrace (23) |

| Infant Row (6) | Reading Room Row (6) | Infant Row (7) | Infant Street (7) |

| California Row (68) | California Row (68) | California Street (68) | California Street (68 |

| Mount Pleasant (20) | Mount Pleasant (20) | Mount Pleasant (20) | Mount Pleasant (58) |

| Australia Row (82) | Australia Row (66) | Australia Street (66) | Australia Street (66) |

| Lononderry Engine Cottages (2) | Londonderry Engine Cottages (2) | Londonderry Engine Cottages (2) | Londonderry Engine Cottages (2) |

| Office Row (53) | Office Row (37) | William Street (30) | William Street (30) |

| Butcher’s Row (40) | Butchers Row (39) | Butcher Street (40) | Butcher Street (40) |

| German Row (22) | German/Doctors Row (66) | Doctor’s Street (66) | Doctor’s Street (66) |

| Bownden Row(23) | Daker’s Row (21) | Post Office Street (21) | Post Office Street (21) |

| Church Row (23) | Church Row (25) | Church Street (26) | Church Street (57) |

| Double Row (32) | Double Row (32) | School Street (32) | School Street (32) |

| Single Row(24) | Railway Row (22) | Bank Head Street (22) | Bank Head Street (22) |

| Model Row (35) | Model Row (27) | Model Street (26) | Model Street (26) |

| New or Cornish Row (57) | Cornish Street (57) | Cornish Street (57) | |

| Henry Street (59) | Henry Street (59) | ||

| Seaham Street (59) | Seaham Street (59) | ||

| Hall Street (50) | Hall Street (50) | ||

| Cooke Street (20) | Cooke Street (20) | ||

| Viceroy Street (61) |

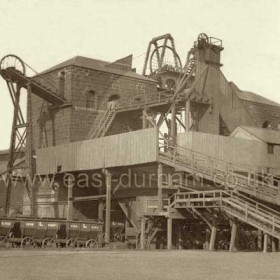

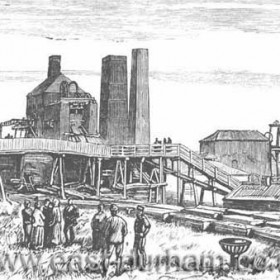

The sinking of Seaton Colliery (the High Pit) by the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company began in 1844 and production of coal commenced in March 1852 after a long and desperate struggle against flooding. The sinking of Seaham Colliery (the Low Pit) by the 3rd. Marquess of Londonderry commenced in 1849 and it began production not long after Seaton though the actual date is not recorded. The two pits were amalgamated as Seaham Colliery under the control of the Londonderry family in November 1864. There were no less than seven known explosions at the pits, before and after amalgamation. There were three in one year at Seaton in 1852, the first year of production, with six men and boys killed in the last of these. One of the casualties was an 8 year old boy. Another explosion at Seaton in 1862 burnt to death two more workers. The massive explosion in October 1871 miraculously killed only 26. Even more miraculously none died in the huge 1872 blast. Finally 164 men and boys were killed in the calamity of September 1880. Though there were no further explosions there were many single or multiple fatalities at Seaham Colliery after 1880 – Seaham’s graveyards are littered with decaying headstones which testify to that grim truth.

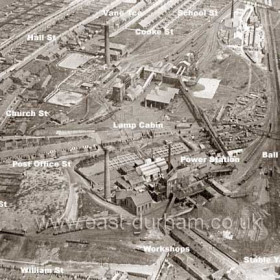

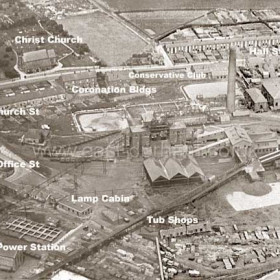

Seaham Colliery Pit Village (New Seaham) was constructed from the mid 1840s onwards and was virtually complete by the time of the 1880 disaster. Another street was built betweeen 1881 and 1891, called Viceroy Street in honour of the office held by the 6th.Marquess of Londonderry from 1886 to 1889. A final small row, Stewart Street (the family name of the Londonderrys), appeared between 1891 and 1895.

By the 1930s much of the housing at Seaham Colliery, cheap and cheerless to begin with, was well past its best and the village was earmarked for wholesale demolition under the Slum Clearance Act. Parkside estate was constructed at the end of that decade and most of the inhabitants transferred en masse to there in 1939/40. Knowing that Westlea and Eastlea council estates were planned to arise on the ruins of their village a few of the inhabitants decided to stay put and wait for the new houses. When war came they were joined by those made homeless in Seaham Harbour by German bombing. The Germans also managed to hit the colliery village, scoring a direct hit on the Seaton Colliery Inn after hours one night in October 1941 and killing the landlady and her friend (this author’s great aunt). Eventually the aptly-named Phoenix was constructed on the site.

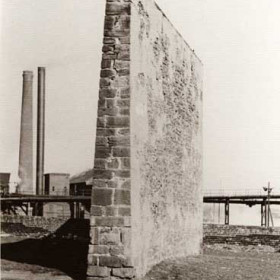

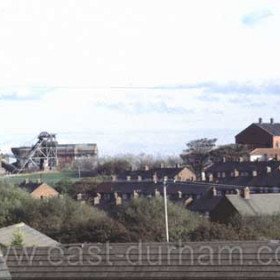

The old pit village was finally swept away between 1945 and 1960 but there are still a few remnants left in 1995 (The Miner’s Hall building, High Colliery School, the row of houses on Station Road which incorporates the New Seaham Inn, now called The Kestrel). The village and most of its inhabitants were gone by 1960 but Seaham Colliery itself survived until the late 1980s. It was nationalised in 1947 after a century of ownership by the Londonderry family. In 1987 Seaham was ‘amalgamated’ with Vane Tempest Colliery and the old pit was relegated to the role of being third and fourth shafts for the newer concern. No more coal was produced at Seaham Colliery. The Seaham/Vane Tempest ‘combine’ was closed by British Coal in 1994 and both sites were cleared. Now there is a great open space where Seaham Colliery stood for 150 years.

History of New Seaham

The preparatory working for the sinking of Seaton Colliery or the High Pit began on July 31 1844. The actual sinking of the shaft commenced on August 12 1845. The mine was developed not by the landowner Lord Londonderry but by the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company, on a site chosen because of its proximity to the Rainton and Seaham waggonway. The main shareholder of this concern was Lord Lambton, 2nd.Earl of Durham, an individual with many other inland pits and who was the second largest producer of coal in County Durham behind Londonderry himself.

The North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company was licensed to exploit only the coal under Londonderry’s land between Seaton and Warden Law, but that canny lord reserved any and all seaward coal for himself. The Marquess it seems was still very nervous about the expense of sinking a new and very deep colliery and preferred others to risk their money in what might yet prove to be a fruitless undertaking. Also, as usual, he was short of cash despite the fact that business was booming. Before very long he had his proof when the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company discovered deep but rich seams of coal.

Sir Ralph Milbanke, he who had sold the estates of Seaham and Dalden to the Irishman for a song a quarter of a century before, must have turned in his grave. Even before this development Lord Londonderry was probably on paper the richest man in the county of Durham. His numerous pits at Penshaw and in the Rainton and Pittington districts and elsewhere in Durham were at their peak and the demand was such that he could usually sell every ton that he produced. Now, almost by accident, he had secured his family’s future for the next century.

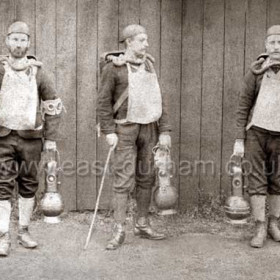

The nearby Mill Inn was known as the ‘Nicky Nack’ and its landlord was dubbed ‘Tommy Nicky-Nack Chilton’ and so Seaton Colliery soon acquired the nickname. Little is known about these early years but a letter survives in the Londonderry Papers at the Durham Record Office which informs us that on January 27 1845 a party of guests travelled from Lord Londonderry’s mansion at Wynyard (near Stockton, now owned by John Hall) to Seaham Harbour to observe the opening ceremony for a new extension to the docks. On the way they passed the digging at Seaton, where a depth of 40 fathoms had been achieved of an anticipated 240 fathoms. At the request of the ladies present two of the ‘sinkers’ ascended from the bottom of the shaft in a large kibble or bucket. They resembled drowned rats more than men but they maintained their dignity and flatly refused to ‘run about and show themselves’ to the spectators.

The pit later made much slower progress due to the water problem. After coal was reached but before it could be exploited a second colliery was begun nearby by the lord of the manor. The reaction of the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company directors to this development has not been preserved but they cannot have been very amused. Nearly thirty years after the first tapping of the concealed coalfield at Hetton the 3rd. Marquess of Londonderry, now 71, at last took the plunge and sank his first deep coal mine. The sinking of Seaham Colliery or the ‘Low Pit’ commenced on April 13 1849. The Low Pit shaft was 1797 feet deep and the High Pit shaft was 1819 feet deep. Both were 14 feet in diameter. The new mines were the second and third deepest in the country (behind Pemberton Main at Monkwearmouth). The first coal from Seaton was only drawn on March 17 1852, after almost seven years of battles against flooding and quicksand. Seaham began producing a little later after a much shorter battle, but the precise date is unknown.

In the first weeks after coming on stream there were three explosions at Seaton, the last of which, on Wednesday June 16 1852, killed six men and boys and injured several others. Among the dead was a 10 year old boy, Charles Halliday or Holliday. The inquest was held at the Mill Inn with Mr.Morton, Agent of the Earl of Durham, present. It was revealed that naked lights (candles) had been used in the pit, nearly four decades after the invention of the safety lamp. The jury recorded a verdict of accidental death.

To justify their huge outlay of money the Londonderrys’ new Seaham pit needed to be a giant in production terms compared to its predecessors inland and this soon proved to be the case. By 1854 (when it had barely begun production and would soon employ far more) 269 hands were employed, making it as large as any of the Rainton and Penshaw pits owned by Lord Londonderry. By the mid-1870s Seaham/Seaton was producing as much coal as all of the other Londonderry pits at Rainton, Pittington and Penshaw combined. By 1880 the mine employed 1500 men and boys and had an output of half a million tons of coal per year. By the time of the census of 1881 some 3,000 people lived in the village of New Seaham.

Charles Stewart, 3rd.Marquess of Londonderry and 1st.Viscount Seaham, died at his home, Holdernesse House in London’s Park Lane, in March 1854. A new place of worship, Christ Church, was built at New Seaham in 1855 by Lady Frances Anne as a memorial to her husband. It is virtually the only monument to the old tyrant that still stands in the town he created. The church received free heating and lighting courtesy of underground pipes from the colliery 200 yards away. Christ Church also included a graveyard which was to become the last resting place for generations of New Seaham inhabitants. Previously the dead had been interred at either the ancient St.Andrew’s at Dalton-le-Dale or the even older St.Mary’s at Old Seaham or the new graveyard at St.John’s in Seaham Harbour.

Like her late husband the Marchioness was infamous for her parsimony and yet on March 1 1856 this complex character entertained between three and four thousand of her pitmen at Chilton Moor. In 1857 she spent over £1000 to entertain 3,930 of her pitmen, dockers, quarrymen and railwaymen at Seaham Hall, in the presence of the Bishop of Durham and numerous friends. Her friend and protege Benjamin Disraeli recognised in his writings after her death that Frances Anne was a tyrant in her way but it would be fairer to describe her as a benevolent despot. As Durham mine owners went the Londonderrys were actually among the best and the miners of the day preferred to work for them than most others. Bad as they were living conditions at New Seaham were far better than most older mining villages in the county. In the 1850s the Marchioness built Londonderry schools at the Raintons, Kelloe, Old Durham, Penshaw and New Seaham (which still stands) and later her son Henry constructed another at Silksworth. She personally paid the teacher’s salaries and all other expenses and allowed the children of non-employees to attend.

The 1850s saw the building of several streets in the vicinity of the two pits and the creation of a tight-knit community. Window tax was abolished in 1851 and mechanised brick production (with machine-pressed bricks) was developed in 1856, both of which made the process cheaper and easier. The typical ‘through terrace house’ at Seaton/Seaham Colliery had one room downstairs and one upstairs (often divided into two by a partition to provide separate sleeping accomodation for boys and girls). The downstairs room served for cooking, bathing, meals, general living and as sleeping space for parents. The back yard had a dry closet privy (a netty) and a coal shed. Social life centred on the back alley. Some of the streets were built and owned by the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company, proprietors of Seaton Colliery. The rest were constructed and owned by the Londonderry family, owners of Seaham Colliery. At this distance in time it is difficult to tell who owned what. The first streets, all of which were mentioned in the 1861 census, were:

West Row: which was later called School Row and later still became Vane Terrace.

School Row: which is not to be confused with School Street (see the below Double Row).

Infant Row: Very small. Only six dwellings.

California Row: 1849 saw the California Gold Rush.

Mount Pleasant : which may have been named after a place in northern Ireland near the Londonderry mansion at Mount Stewart or simply because it occupied a good vantage down to the sea.

Australia Row: Australia was a principal destination for British emigrants in this period, especially miners from the northeast of England. Many of them promptly commemorated their roots by naming their new communities after the ones they had left behind. A Newcastle, a Sunderland, a Murton, a Ryhope and yes even a Seaham, were created in New South Wales and survive to this day.

Office Row: which was later called William Street.

Butcher’s Row: Butcher may have been a director/official of the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company

German Row: later called Doctor’s Street, which in the direction of Sunderland had a fine view of the North Sea (The German Ocean.).

Bownden Row: later called Daker’s Row and later still renamed Post Office Street. Bownden may have been a director/official of the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company.

Church Row: which faced the new Christ Church

Double Row: later called School Street

Single Row: later called Railway Row, later still renamed Bank Head Street

Model Row: Presumably the builders and owners were proud of this street and gave it a magnificent title.Or maybe they had just run out of names !

Seaton and Seaham Collieries (New Seaham) and Seaham Harbour remained quite separate communities, divided by fields, and connected only by the Rainton & Seaham Railway and a dirt track and the fact of shared ownership by the Londonderrys. In 1863 a Local Board of Health was created to conduct Greater Seaham’s affairs. It was led from 1873-94 by J.B.Eminson, chief financial agent for the Londonderrys in Seaham from 1869-96. The Board became Seaham Harbour Urban District Council by the Local Government Act of 1894. Eminson also led the new body from 1895-96. During his 27 years service he filled the leading position in the town. He was also Chairman of Seaham Magistrates and a member of the Easington Guardians (Work House). Despite the semblance of a kind of democracy after 1863 Greater Seaham was still a family fiefdom.

At Hartley Colliery in Northumberland in January 1862 over 200 men and boys died of suffocation when the only shaft was blocked by falling machinery. Shortly after this disaster, the greatest single loss of life in the Great Northern Coalfield, the Seaton High Pit and Seaham Low Pit were joined by an underground link. Within weeks, on March 29, a cage rope broke at the Low Pit and the shaft was blocked by stone. Over 400 men and boys and 70 ponies escaped via the High Pit. They would have shared the fate of the Hartley colliers and perished within hours without the connection. The Northumberland and Durham Miner’s Permanent Relief Fund had its origin in the widespread need which followed the Hartley Disaster. Before Hartley it was the individual worker’s resposibility to subscribe to a ‘club’ to cover ‘private’ medical expenses. There were discretionary payments from the mineowners, at a level below that of wages, for some workers who suffered an accident, with the limited objective of retaining the services of skilled workmen temporarily disabled. For those permanently crippled or worse there was nothing and before long they and/or their widows and children were given their marching orders from their colliery houses. The Employer’s Liability Act was still 20 years in the future.

Another explosion on April 6 1864 at Seaton Colliery severely burnt two men, Tristram Heppell and William Fairley. Both died in agony in their homes some days later. Heppell’s father, a master sinker of pits, had been a contemporary and friend of George Stephenson at Killingworth Colliery in Northumberland. Heppell was a member of the Seaham Volunteers and so was given a military funeral at St. Mary’s. Reverend Angus Bethune conducted the service. We shall come across this individual again later in this narrative.

When an Act of Parliament prohibited the working of coal-mines without two outlets from each seam Lady Frances Anne decided that the simplest way to comply with this legislation in the case of Seaham Colliery was to buy Seaton Colliery from the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company and amalgamate it with Seaham. This was done in November 1864, and was virtually the last business deal she completed for she was dying by then. She died at Seaham Hall on January 20 1865, three days after her 65th.birthday. Her collieries passed to her son Henry, Earl Vane, who succeeded his half-brother Frederick as Marquess of Londonderry in 1872.

‘Observer’, who wrote ‘Gleanings from the Pit Villages’ in 1866, gave Seaham Colliery high praise in contrast to older Durham pit villages. He commended its roomy dwellings, good gardens and wide streets. The usual outdoor meeting place for men at Seaham Colliery in dispute with the management was the ball alley. This was also used for gambling, fist-fights and games of hand-ball against teams from neighbouring collieries. The surface of the wall eventually deteriorated and it was abandoned to nesting birds in the 1920s.

As the North Hetton and Grange Colliery Company no longer had an interest in the Seaton part of Seaham Colliery or its housing stock any trace of that concern in the street names of the village was now removed by the Londonderrys. Uncharacteristically they did not bestow their own names as had happened at Seaham Harbour and other places, at least not yet: West Row became School Row and only later became Vane Terrace; Infant Row became Reading Room Row; Bownden Row became Daker’s (the new manager of Seaham Colliery) Row; Single Row became Railway Row. One new street appeared, predictably being called New Row. By the time of the 1881 census it had become Cornish Row in honour of the wave of immigrants coming in from that county.

All of the Easington district collieries began to receive a steady stream of Cornishmen and Devonians and their families in the mid-1860s. A street would be eventually be named in honour of the Cornish at Seaham Colliery and a whole district of Murton was taken over by these refugees from the dying lead and tin industries and nicknamed O’Cornwall. Wingate Grange Colliery also received a very large contingent. Seaham Colliery also absorbed Scots, Irish and Welsh and also a group from Norfolk. Wood Dalling and neighbouring villages must have been stripped bare of their agricultural labourers, lured north by the prospect of higher and consistent wages by the agents of the Marquess of Londonderry and other coalowners. Most of these people would retain their accents for the rest of their lives but their children and grandchildren were completely assimilated into the host community and became Geordies. Seaham Colliery must have been a very cosmopolitan place in these early days and it cannot have been unusual to hear a dozen accents during a day’s work at the pit.

The mother and stepfather of the alleged mass murderess Mary Ann Cotton moved to New Seaham from South Hetton in the early 1860s. George and Margaret Stott took up residence in California Street at an unknown number and in the summer of 1865 took in Mary Ann’s only surviving child, Isabella Mowbray, aged 6. Mary Ann had lost her husband William Mowbray to typhus in Hendon at the start of the year and her other daughter Margaret Jane had succumbed to the same disease at Seaham Harbour in May. Now Mary Ann needed time to sort herself out and farmed her child out to its grandmother and step-grandfather. She moved to Sunderland and got a job as a nurse at the Infirmary. There she met a patient, George Ward, and married him before the year was out. Mysteriously he was dead within months of a disease which apparently baffled his doctors. At the end of 1866, within weeks of being widowed a second time, she took a job at Pallion as housekeeper to a well-to-do shipyard official James Robinson, who had just lost his own wife and badly needed female help with his five children. The youngest of these, a sickly infant boy, died within days of her arrival.

A few weeks later, in the spring of 1867 Mary Ann, a “nurse” remember, was summoned back to New Seaham to look after her mother who was dying of the liver disease hepatitis. Margaret Stott expired within a week and was buried at New Seaham Christ Church. Mary Ann then quarrelled with her stepfather over a few sheets she claimed had been hers. He had never liked her much and now told her what he thought of her and ordered her to leave his house and take her child with her. George Stott already had eyes on a comely widow, Hannah Paley, who lived in the same street, and he didn’t want the little girl around cramping his style. He married Hannah Paley not long after but Mary Ann was not invited to the wedding and in fact never came to Seaham again. Within weeks of Mary Ann’s return to Pallion, Isabella Mowbray was dead, two more of Robinson’s children also, and the “housekeeper” was pregnant by her employer. George Stott did see his stepdaughter one more time. He was her last visitor in the condemned cell at Durham Gaol in March 1873 a few days before she was hanged for the murder of yet another child, a son of her fourth (bigamous) husband Frederick Cotton. Her mother Margaret Stott and her daughter Isabella Mowbray are included among the 21 people that Mary Ann Cotton has been accused of murdering either for the insurance money or because they were somehow in her way.

The first mass meeeting of the lodges of the new union, the DMA (Durham Miners’ Association), took place at Wharton Park in the city of Durham in July 1871. Just three months later on Wednesday October 25 1871 26 men and boys were killed in another explosion at Seaham Colliery. On the day before the tragedy a mass meeting of young men and boys had determined to ask for some alteration in their bonds – in particular a reduction in their hours of labour. For many below the rank of hewer the working day lasted from their rising at 3am until they returned home filthy at about 6.15pm. There was barely time for any relaxation before going to bed. A deputation was sent to see the manager Dakers but he refused to give them an answer until the next conclusion of the bond in April 1872. Dakers refused even to see a second delegation.In consequence a mass meeting of all the men and boys was called for the Thursday night with a view to laying the pit idle. The disaster intervened.

The explosion of Wednesday October 25 1871 occurred at 11.30 pm, otherwise the death-toll would have been much higher – by now the colliery was employing 1100 men and boys. The shock was felt at Seaham Harbour.John Clark, aged 9, sitting on the surface in a cabin near the pit shaft, was blown 10 yards by the explosion. The force of the blast was such that many ponies were killed in their underground stables 1.5 miles away from the epicentre. Two men named Hutchinson, father and son, working as ‘marrows’ (marras), fired the shot which triggered the blast. The father, Thomas senior, survived the explosion but was badly injured. For days he hovered between life and death and medical opinion concluded that he could not survive. But survive he did – for he was destined to be killed in the 1880 explosion. Thomas Hutchinson junior left a pregnant widow and two children. Manager Dakers and Head Viewer Vincent Corbett went down the pit to assess the situation and made a decision which to some seemed harsh and to others seemed like murder. The ‘stoppings’ were rushed up to starve the fire of oxygen and save the mine irrespective of the men thereby entombed. The explosion occurred on Wednesday – by Sunday the furnace was re-lighted at the shaft bottom for ventilation. The men were somehow persuaded to return to work while the bodies of their colleagues lay entombed for several weeks in nearby workings. Religious decency then laid much greater emphasis on proper burial of a body in consecrated ground.Four of the bodies were brought out immediately after the explosion but the remaining 22 were not recovered until December 20. The appeal fund produced just over £2,000. The inquest was held at the New Seaham Inn (now called the Kestrel). Verdict – Accidental death. Just as the village began to recover from the tragedy it was struck another mortal blow with an outbreak of smallpox. There was another explosion in 1872 but there was no loss of life or injury.

Manager Dakers either retired, died or moved on at the start of 1874. He was replaced by a 21 year old, Mr.Thomas Henry Marshall Stratton, who was fated to be in charge when the 1880 disaster occurred. By then he was still only 28 and due to move on from Seaham Colliery to his next post. The man had no luck. There was another county-wide coal strike in 1879, the first major confrontation since the the Great Strike of 1844 and, as usual, the miners were defeated. Before the village of Seaham Colliery could properly recover from this ruinous episode an even greater disaster struck in the following year. The death of one collier started a train of events which led to an immense tragedy. A man called Robert Guy was run over and killed by a set of tubs on the Maudlin engine-plane at Seaham Colliery on August 7 1880. Adverse and critical remarks made at the inquest a few days later obliged manager Stratton to have refuge holes from the rolling tubs made larger and more frequent to prevent a recurrence of the tragedy. This work went on for several weeks and it may well have been a shot fired in the course of it which triggered the great explosion.

In that hot August of 1880 the Seaham Volunteer Artillery Brigade distinguished itself in the big gun shooting of the National Artillery Competition at Shoeburyness, picking up a beautiful trophy and over £200 in prize money, a very handsome sum in those days. The team members were welcomed back to Seaham as heroes and their crackshot Corporal Hindson was carried shoulder-high through the town. The next big event in the town’s social calendar was Seaham’s Annual Flower Show, to be held in the grounds of Seaham Hall from Thursday September 9 to Sunday the 11th. The 5th.Marquess himself, a rather shy and unassuming man, was to make one of his rare visits in order to present the prizes. Indeed he was to honour the town his parents had founded with his presence for an entire week. As it turned out he was to stay for a good deal longer than he anticipated. Many of the miners at Seaham Colliery had entries in the show and some of these men swapped shifts with those disinterested in horticultural affairs in order that they might attend. It was to prove a fateful decision for those who should have been working on the Tuesday/Wednesday night and for those who ended up working when ordinarily they would have been at home sound asleep.

At Seaham Colliery there were three shifts per day for hewers (everyone else worked much longer hours) of 7 hours each, covering the period from 4 am to 11.30 pm. The shifts were: 1) Fore Shift, 4 am to 11.30 am 2) Back Shift, 10 am to 5.30 pm 3) Night Shift, 4 pm to 11.30 pm. Each shift involved some 500 men and boys and at the overlap of the shifts there could be over 1,000 men in the pit. From 10 pm to 6 am, when the colliery was comparatively quiet, was the maintenance shift, which employed far fewer workers. Fortuitously the 1880 explosion took place at 2.20 am during one such maintenance shift, 100 minutes before the start of the Fore shift, which is why only 231 men and boys were below ground.The tragedy could have been much much worse, eclipsing the disasters at Hartley and West Stanley